Sesame Street.

If it sounds odd that an adult would go to see a movie about a puppet then you probably don't have children or grandchildren. Elmo has been a ubiquitous part of children's pop-culture since Kevin Clash took over his character in 1985. His

message of love and the joy of relationships has made him one of the most recognizable "Sesame Street" characters.

Being a puppeteer is not easy work, and it requires tremendous creativity to bring personality to a puppet. The film chronicled Kevin Clash's journey from growing up in Baltimore to getting his big break on WMAR in Baltimore, then the

"Captain Kangaroo" show, and finally on Sesame Street where he has moved up to be co-executive producer. I found the story to be inspiring and it spoke to me as an artist who strives to bring creativitivity and individuality to a group.

The film also brought back some nice memories of my own brief encounter with Elmo. Several years ago, the Boston Pops Orchestra filmed a television show with actors and muppets from "Sesame Street." Elmo/Kevin Clash was there, and it was the first

time I saw Muppets being worked from behind a small stage. I was fascinated as I could watch Clash looking at a TV monitor as he was manipulating his Elmo puppet. Most of all, I was surprised to see that the high, squeaky voice of Elmo was made by a man of NFL linebacker frame.

A highlight was being asked to come up front during the show to interact with some of the Sesame Street cast and Elmo, in a variation of the song, "Who are the People in Your Neighborhood?" which, for the Pops TV show, was changed to,

"What are the Instruments in the Orchestra?" I and a few other colleagues (Larry Wolfe, bass, Tom Gauger and Frank Epstein, percussion) went up front to play a little on our instruments while the song was being sung. The photo at above, left,

shows a moment from the rehearsal for the TV show. You can see (left to right), Bob, Elmo, conductor Keith Lockhart, me, Maria, Larry Wolfe, Gordon and Alan. It was a fun moment, which also brought back nice memories of my first concert with

the Baltimore Symphony, at which Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch (with Caroll Spinney behind the Muppets) were part of the concert (Big Bird conducted one piece on the concert, giving me the opportunity to say that in my career, I've been conducted by

Big Bird and Leonard Bernstein, a line I've used in several interviews).

If you have a chance to see "Being Elmo," do so. It's a great story that's well put together. I left smiling and inspired by creativity. I think you would, too.

November 26, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Last month, I travelled to France to take part in the first scholarly symposium devoted to the serpent, an event that was organized on a very high level and which represents one of the most significant moments relating to this most

fascinating instruments in its over 400 year history.

Last month, I travelled to France to take part in the first scholarly symposium devoted to the serpent, an event that was organized on a very high level and which represents one of the most significant moments relating to this most

fascinating instruments in its over 400 year history.

The Symposium, Le Serpent sans Sornettes, was organized by Florence Getreau, Cecele Davy-Rigoux and Volny Hostiou, and was sponsored by le musee de l'Armee and l'Institute de recerche sur le patrimoine musical en France

(CNRS/BnF/ministere de la Culture). Planning had been going on for several years, and the conference organizers put together an extremely rewarding program of papers and concerts that ranks among the most inspiring musical events I have ever attended.

My trip began in Rouen, France, where I gave a trombone masterclass at the Rouen Conservatorie and also played serpent with a group of students and faculty from the Conservatoire. In addition to presenting a paper at the Paris Symposium,

I also planned to lead a concert of 18th century music for winds with serpent, and we rehearsed the group and gave a concert in Rouen before travelling to Paris to present the same program. I was very impressed with the high quality of playing

by this group, and had the happy experience of sitting next to players of French bassoons (most American orchestral bassoon players use German bassoons). The group was put together by my friend, Volny Hostiou, who is professor of tuba,

euphonium and serpent at the Conservatoire.

My trombone masterclass in Rouen was also a very nice event. The trombone professor at the Conservatoire is Nicolas Lapierre, and all of his students attended the all-day masterclass I presented. I played and talked about several

concepts, and then interacted with many students who played for me. The photo above at left shows me leading the class in a group warm up; Professor Lapierre is on the left of the group. There is a long history of French players in the Boston Symphony, and I was happy to present Professor Lapierre with photographs of several Boston Symphony trombonists,

most notably Joannes Rochut and Eugene Adam. Of note was the fact that several students played "Solo de Concours" by Croce-Spinelli, the very piece with which Adam won first prize in trombone at the Paris Conservatorire in 1903. Nice

connections all around.

My trombone masterclass in Rouen was also a very nice event. The trombone professor at the Conservatoire is Nicolas Lapierre, and all of his students attended the all-day masterclass I presented. I played and talked about several

concepts, and then interacted with many students who played for me. The photo above at left shows me leading the class in a group warm up; Professor Lapierre is on the left of the group. There is a long history of French players in the Boston Symphony, and I was happy to present Professor Lapierre with photographs of several Boston Symphony trombonists,

most notably Joannes Rochut and Eugene Adam. Of note was the fact that several students played "Solo de Concours" by Croce-Spinelli, the very piece with which Adam won first prize in trombone at the Paris Conservatorire in 1903. Nice

connections all around.

I should mention at this point that my oldest daughter, Linda, accompanied me on the trip. Linda studied French throughout school, and having her with me on her first trip to France was a joy. And I was grateful more than once that it was

Linda, not me, talking to cab drivers and ordering food - in French - which ensured we got where we wanted and the food we thought we ordered. We had built in some time for sightseeing on the trip and while I had been to France several times

while on tour with the Boston Symphony, it was a special joy to share this time with my daughter who was seeing it all for the first time. The photo at left shows us on top of the old clock tower in Rouen, overlooking the Cathedral.

I should mention at this point that my oldest daughter, Linda, accompanied me on the trip. Linda studied French throughout school, and having her with me on her first trip to France was a joy. And I was grateful more than once that it was

Linda, not me, talking to cab drivers and ordering food - in French - which ensured we got where we wanted and the food we thought we ordered. We had built in some time for sightseeing on the trip and while I had been to France several times

while on tour with the Boston Symphony, it was a special joy to share this time with my daughter who was seeing it all for the first time. The photo at left shows us on top of the old clock tower in Rouen, overlooking the Cathedral.

Rouen is a beautiful city, full of history (it is the city where Joan of Arc was tried and burned at the stake) and striking art and architecture. The cathedral is notable not only for its beauty, but for the fact that Claude Monet painted over

20 paintings of the west front of the cathedral. I have a particular fascination of gothic cathedrals, so it was nice to visit Rouen's cathedral which was new to me. Especially interesting was the Abbey of St. Ouen. This church is no longer

used for worship, but is nearly as big as the cathedral in Rouen. Of particular interest to me was a beautiful painting of a serpent playing angel, high up on the ceiling of one of the side chapels off the ambulatory on the south side (photo, right). This is the only bit of

painting left on any of the chapel ceilings, and it is very large as well; the angel is over six feet high. The detail is striking, and the serpent is beautifully rendered. It was a strong moment, seeing this painting of an instrument that

was used in worship in the Abbey for so many years, a survivor of the ravages of time.

It is difficult to describe the impact of the Symposium in Paris. But I will try.

The Symposium was held in the Musee de l'Armee in Hotel des Invalides on October 6 & 7. This is the place where Napoleon Bonaparte is buried. The impact of the setting was dramatic. To walk each day to the

conference room (which was superbly equipped with the latest technological advances in projections and sound) and see the golden dome over Napoleon's tomb was breathtaking. Over the two days of the conference, over 20 papers were presented

by scholars from around the world - representatives from France, England, Germany, Italy and the USA. Conference participants came from other countries as well, and it was nice to see many friends there who I had met at other conferences and

concerts over the years. My paper was titled, Quires and Bands: The Serpent in England and gave an overview of the use and manufacturing of the serpent fromt the late 19th century to the present. I also spoke about the modern

revival of the serpent which started in the 1970s with the late Christopher Monk. I was pleased that my paper was so well received, and it will be published next year in a book of the conference proceedings.

The Symposium was held in the Musee de l'Armee in Hotel des Invalides on October 6 & 7. This is the place where Napoleon Bonaparte is buried. The impact of the setting was dramatic. To walk each day to the

conference room (which was superbly equipped with the latest technological advances in projections and sound) and see the golden dome over Napoleon's tomb was breathtaking. Over the two days of the conference, over 20 papers were presented

by scholars from around the world - representatives from France, England, Germany, Italy and the USA. Conference participants came from other countries as well, and it was nice to see many friends there who I had met at other conferences and

concerts over the years. My paper was titled, Quires and Bands: The Serpent in England and gave an overview of the use and manufacturing of the serpent fromt the late 19th century to the present. I also spoke about the modern

revival of the serpent which started in the 1970s with the late Christopher Monk. I was pleased that my paper was so well received, and it will be published next year in a book of the conference proceedings.

Other papers focused on the serpent in France, early method books for the serpent, serpent manufacture and many more subjects. My friend, Bruno Kampmann, presented a paper about upright forms of serpents, and he asked me to demonstrate

several examples of instruments he had brought along from his considerable collection. All of this added greatly to my own knowledge of the serpent, and the interaction with other scholars during breaks and at meals provided fertile ground for

questions and ongoing discussion. The papers were of a very high level of scholarship, and with was wonderful to be a part of such a distinguished group of scholars.

Another highlight of the Symposium was several concerts that were organized and presented. In addition to my own concert of chamber music for winds (photo, right), we heard a concert of chant and early music with serpentists Volny Hostiou and Michel Negre (with two superb choirs), a program of improvisation by Michel Godard and

Linda Bsiri, and a new piece by Benjamin Attahir for string quartet and winds with Patrick Wibart on serpent. These concerts were inspiring to say the least, showing the serpent in many of its uses since its invention in the 16th century

as an instrument to accompany chant in the church. While I have dozens of recordings of serpent players - including those who gave concerts at the conference - it was great to see these players up close, to talk to them about their instruments, mouthpieces and fingering choices, and to hear their

playing in such dramatic settings. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the concert of chant I heard in the Cathdral of St. Louis at les Invalides was one of the most rewarding musical experiences of my life.

Another highlight of the Symposium was several concerts that were organized and presented. In addition to my own concert of chamber music for winds (photo, right), we heard a concert of chant and early music with serpentists Volny Hostiou and Michel Negre (with two superb choirs), a program of improvisation by Michel Godard and

Linda Bsiri, and a new piece by Benjamin Attahir for string quartet and winds with Patrick Wibart on serpent. These concerts were inspiring to say the least, showing the serpent in many of its uses since its invention in the 16th century

as an instrument to accompany chant in the church. While I have dozens of recordings of serpent players - including those who gave concerts at the conference - it was great to see these players up close, to talk to them about their instruments, mouthpieces and fingering choices, and to hear their

playing in such dramatic settings. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the concert of chant I heard in the Cathdral of St. Louis at les Invalides was one of the most rewarding musical experiences of my life.

Linda and I enjoyed a day of sight seeing after the Symposium, taking in as many things as our legs could support in a full day of travelling around Paris. We returned home satisfied and inspired, with many thoughts to consider about the serpent

and its place in history.

Upon my return, I wrote a brief report about the Symposium for the Historic Brass Society Journal which may be read by clicking

HERE. The report also includes several more photos of the Symposium.

The Historic Brass Society has also made the complete program from the Symposium (with programs of all of the concerts) available as a PDF file; it can be viewed and downloaded by clicking

HERE.

November 25, 2011 - NEW

I have had a fascination with the Trombone Concerto written for Tommy Dorsey by Nathaniel Shilkret since I was in high school in the 1960s. The piece was a rare instance of "classical crossover" by the "sentimental gentleman

of swing," who gave the premiere of the piece with the New York City Symphony conducted by Leopold Stokowski on February 15, 1945. I first learned of the piece when reading a biography of Stokowski many years ago. As a young boy, I made several futile attempts

to contact

Nathaniel Shilkret Music but over time, my interest turned to other things. But in the last decade, the Shilkret Concerto has found new life, thanks in no small part to Bryan Free, who worked with Shilkret's family to reconstruct

the Concerto from old recordings and manuscripts. Free's story is told in an article he wrote for the International Trombone Association Journal, Nathaniel Shikret's Trombone Concerto: A Rediscovery Process (Volume

29, Number 1, Winter 2001).

I have had a fascination with the Trombone Concerto written for Tommy Dorsey by Nathaniel Shilkret since I was in high school in the 1960s. The piece was a rare instance of "classical crossover" by the "sentimental gentleman

of swing," who gave the premiere of the piece with the New York City Symphony conducted by Leopold Stokowski on February 15, 1945. I first learned of the piece when reading a biography of Stokowski many years ago. As a young boy, I made several futile attempts

to contact

Nathaniel Shilkret Music but over time, my interest turned to other things. But in the last decade, the Shilkret Concerto has found new life, thanks in no small part to Bryan Free, who worked with Shilkret's family to reconstruct

the Concerto from old recordings and manuscripts. Free's story is told in an article he wrote for the International Trombone Association Journal, Nathaniel Shikret's Trombone Concerto: A Rediscovery Process (Volume

29, Number 1, Winter 2001).

Shikret's Concerto has been strongly championed by Jim Pugh, one of the finest trombonists of our time, who gave the first performance of the Concerto in modern times with Skitch Henderson and the New York Pops on

January 17, 2003. This was followed by a superb recording by Pugh with the Colorado Philharmonic (conducted by Jeff Tyzik)

that I reviewed in the Online Trombone Journal.

All of this background about this important and fascinating part of the trombone's repertoire and history is lead up to the photograph at left (the back of the photo confirms it is an origional print from 1945). I have seen several images that surrounded Tommy Dorsey's performance of Shilkret's Concerto but last week,

I noticed that ebay was auctioning an original Associated Press Wire Photo of Tommy Dorsey, Leopold Stokowski and Nathaniel Shilkret. It is a tremendous photograph, with Stokowski in a stylized conductorial pose, and Dorsey reading the solo part for

the Concerto over Shilkret's shoulder. I had never seen this photograph before so I bid and and was pleased to win the auction. It's a terrific image raises a lot of questions about the three personalities involved.

The sidebar on the right side of the photo is part of the image, included by the AP, and reads:

(NY19) NEW YORK, Feb. 6_ _ CLASSICS AND SWING GET TOGETHER _ _ Leopold Stokowski (right), conductor of the New York City Symphony Orchestra, supervises a rehearsal by Tommy Dorsey, swing trombonist,

who will be guest soloist with the orchestra February 15 (AP Wirephoto) (CCL31935 STF-TF) 1945.

After doing a little research, I have found this image available directly from the AP in a variety of sizes in a modern print; for more information, click

HERE.

October 28, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Today, I received my monthly copy of The International Musician, the magazine of the American Federations of Musicians (musician's labor union). In the back of each issue, symphony orchestras advertise auditions for open positions. And

this issue contained an advertisement that has not been seen in the pages of The International Musician for nearly 30 years - an announcement from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, advertising a vacancy for Bass Trombone (image at left).

That's my chair.

Today, I received my monthly copy of The International Musician, the magazine of the American Federations of Musicians (musician's labor union). In the back of each issue, symphony orchestras advertise auditions for open positions. And

this issue contained an advertisement that has not been seen in the pages of The International Musician for nearly 30 years - an announcement from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, advertising a vacancy for Bass Trombone (image at left).

That's my chair.

Well, it is now. And has been since May 1985. But come August 27, 2012, someone else will sit in that chair and continue the tradition of bass trombone playing in the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Seeing the advertisement today brought back a lot of memories, back to the time when I saw a similar ad in 1984 advertising the same position (image at right). I remember the thrill of opening up The International Musician and seeing

the announcement there before me. I cut it out and put it on my music stand, a daily reminder of what I was working toward. Today, some bass trombone player somewhere in the world is very likely looking at this new advertisement, and perhaps

has cut it out of the current issue and taped it to HIS (or HER) music stand. In March 2012, we hope to be able to announce my successor so the chain of bass trombone players in the BSO can continue unbroken after I leave next August.

When I compared the ads for auditions in 1984 and 2012, I was struck by several changes. When I joined the orchestra, Seiji Ozawa was music director; today, the BSO has no music director, and is in the midst of a search to find a successor to

James Levine. Yet Seiji Ozawa's name appears in both ads, a testament to his long association with the orchdestra. John Williams was the conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1984; today it is Keith Lockhart. Back in 1984, I had to make

a taped audition before being invited to the live preliminary round; today candidates may have to make a CD recording. An email address is given on the new ad, and resumes can be submitted as a WORD file or a PDF; back in 1984, words like email,

WORD and PDF were not part of our vocabulary.

Yet one thing is the same: each advertisement sent the community of bass trombonists to the practice room. If you're reading this and planning to take the audition, I wish you well in your preparation. I hope to have the opportunity to shake the hand of the person who

wins the audition next March. And I pray you will have a career in Boston as satisfying as I have had, playing daily with one of the world's greatest orchestras in one of the finest concert halls, Symphony Hall. Now, stop reading and get back

to practicing!

October 28, 2011 - NEW

The School of Music of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts of Arizona State University has announced my appointment as Professor of Trombone, effective fall, 2012. I have added a page on my website with a link to the

official ASU announcement of my appointment, as well as other information; that page may be found

HERE.

September 27, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Over the years, I have been very fortunate to be able to travel around the world with a trombone in my hand. Tours with the Boston Symphony Orchestra have been a big part of this, but I have also travelled on vacation, and at the invitation

of YAMAHA, colleges, universities and symphony orchestras who ask me to do some teaching or performing in various countries.

Over the years, I have been very fortunate to be able to travel around the world with a trombone in my hand. Tours with the Boston Symphony Orchestra have been a big part of this, but I have also travelled on vacation, and at the invitation

of YAMAHA, colleges, universities and symphony orchestras who ask me to do some teaching or performing in various countries.

Last week, I was in Iceland, at the invitation of the

Iceland Symphony Orchestra,

who had asked me to come to play with their orchestra in a performance of Janacek's Sinfonietta. That piece requires two bass trombone players, and

when Oddur Björnsson, the Iceland Symphony's principal trombone player, asked me if I would be able to come over and play in their section, it took only a few seconds to say yes. Fitting in nicely with my vacation from the Boston Symphony

Orchestra, my wife and I traveled to Reykjavik for what proved to be a very enjoyable and enlightening week in Iceland.

Playing the concert with the Iceland Symphony was certainly a highlight of the trip. The photo above, right, shows the low brass section for the performance (left to right): Oddur Björnsson (principal), Sigurður Þorbergsson, David Broboff, me, and Austin Howle (tuba).

It is a fine section and while I had played the piece with the Boston Symphony on many occasions, it was enlightening to play it with another orchestra, and fit into their own unique style of playing and approaching making music. It was

a great pleasure to work with this fine section in their beautiful new concert hall, Harpa, and enjoy making great music together.

Playing the concert with the Iceland Symphony was certainly a highlight of the trip. The photo above, right, shows the low brass section for the performance (left to right): Oddur Björnsson (principal), Sigurður Þorbergsson, David Broboff, me, and Austin Howle (tuba).

It is a fine section and while I had played the piece with the Boston Symphony on many occasions, it was enlightening to play it with another orchestra, and fit into their own unique style of playing and approaching making music. It was

a great pleasure to work with this fine section in their beautiful new concert hall, Harpa, and enjoy making great music together.

Yet playing with the Iceland Symphony was just the beginning of the adventures my wife and I had in Iceland. While that little country was put on the map - so to speak - in a big way when the volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted last year and disrupted

air traffic throughout the world for several weeks, Iceland has long been known for its spectacular natural beauty. While we stayed in Reykjavik, we were able to get out of the city for several long days of excursions, enjoying some of the

spectacular Icelandic landscape.

The photo above, left, shows the scene at Þingvellir, the site of the world's oldest known Parliament, from about 870 AD. While this place has great significance for Icelanders - when the modern Icelandic Republic achieved its independence

from Denmark on June 17, 1944, the moment was celebrated at the Law Rock at Þingvellir - it is also the place where you can clearly see the effects of ongoing seismic activity. It is the place where the American and Eurasian tectonic plates

are slowly moving apart. This has resulted in dramatic fissures in the ground - some small and some very, very large - that create a dramatic, rugged landscape.

The photo above, left, shows the scene at Þingvellir, the site of the world's oldest known Parliament, from about 870 AD. While this place has great significance for Icelanders - when the modern Icelandic Republic achieved its independence

from Denmark on June 17, 1944, the moment was celebrated at the Law Rock at Þingvellir - it is also the place where you can clearly see the effects of ongoing seismic activity. It is the place where the American and Eurasian tectonic plates

are slowly moving apart. This has resulted in dramatic fissures in the ground - some small and some very, very large - that create a dramatic, rugged landscape.

I have seen many impressive waterfalls in my life - Niagara Falls in the USA/Canada, waterfalls in Yosemite and Yellowstone National Parks, and Iguazu Falls in Brazil/Paraguay/Argentina come to mind - but I was unprepared to encounter Gullfoss

(right). Its name means "Golden Waterfall." When Oddur drove Pat and me to see this tremendous waterfall, the sound was immediately evident even before we saw the water. As we got closer, a dramatic sight unfolded before us - a multi-tiered waterfall

that took your breath away. As we walked along the path - and walked to several other vantage points - various elements of Gullfoss came to view. The rocky terrain added to the drama of this remarkable turn in the flow of a river. I think I could

have stayed at Gullfoss all day long - it was so impressive and powerful and conjured up many thoughts in my mind as I considered the remarkable diversity of Creation.

I have seen many impressive waterfalls in my life - Niagara Falls in the USA/Canada, waterfalls in Yosemite and Yellowstone National Parks, and Iguazu Falls in Brazil/Paraguay/Argentina come to mind - but I was unprepared to encounter Gullfoss

(right). Its name means "Golden Waterfall." When Oddur drove Pat and me to see this tremendous waterfall, the sound was immediately evident even before we saw the water. As we got closer, a dramatic sight unfolded before us - a multi-tiered waterfall

that took your breath away. As we walked along the path - and walked to several other vantage points - various elements of Gullfoss came to view. The rocky terrain added to the drama of this remarkable turn in the flow of a river. I think I could

have stayed at Gullfoss all day long - it was so impressive and powerful and conjured up many thoughts in my mind as I considered the remarkable diversity of Creation.

In a complete contrast to Gullfoss was Seljalandsfoss (left), another waterfall that was among the most unique I have ever seen. This is one of the highest waterfalls in Iceland, but is unique because you can walk BEHIND the waterfall. Erosion from the

falling water has created an unusual cavern behind the waterfall where you can walk and see the water from a completely different angle. The several "fingers" of water that flowed over the cliffside made for a beautiful cascade as the water pounded to the ground

and ultimately out to sea.

These natural wonders were stunning in every way, but on our last full day in Iceland, we joined a group to walk ON Solheimajökull glacier (right). We have been up close to glaciers in the past - in Glacier National Park in Montana, USA, and at Lake Louise

in Canada. But we had never walked ON a glacier before. This was a unique opportunity for us. Equipped with crampons (spikes that were strapped to our hiking boots) and an ice pick, we spent nearly four hours hiking on the glacier, and learning so much about

how glaciers move and work. Like most glaciers, this glacier was not stereotypically "clean" - rather it was covered with volcanic ash and rocks that it picked up in its long march down hill. Glaciers pick up, crush and move anything in their path,

and as a result, a glacier is full of all manner of rocks and stones. We walked among large peaks of ice covered with volcanic ash, and past large crevasses and holes in the ice. We had a sure-footed and expert guide to navigate us through the

potentially dangerous landscape. At one moment, he pointed out how the ice had become very thin, creating a cave just inches under the surface. The walk was tiring but inspiring, and we were so happy to have shared in such a unique

experience. We will never look at ice again the same way.

These great natural wonders are just a sample of what we saw in the Icelandic country side. We saw the Eyjafjallajökull volcano from a short distance, and herds of cattle and sheep at farms. Rural churches, more waterfalls and so much more

greeted us. Yet Reykjavik had many things for us to enjoy as well. It is a small city, with about 200,000 people living in it. Most buildings are low and no more than 2-4 stories high - reflective of the awareness of earthquake

activity in the area. The tallest building in Reykjavik is the stunning

Hallgrímskirkja

(left), a Lutheran church whose dramatic profile dominates the Reykjavik skyline. Some remark that it looks like a Space Shuttle, but it was designed in

the 1930s, long before the Space Shuttle was even an idea. Rather, its design is taken from massive basalt columns found in various parts of Iceland's natural landscape. Inside, it is dramatic in its simplicity, and we heard its 5000 pipe organ being played by

two of the church's organists - a thrill for sure. We also went to the top of the spire where the observation platform gave us dramatic views of the surrounding area - sea, mountains, houses, docks and so much more. We also visited

several museums that taught us a lot about Iceland, its land, culture and people.

These great natural wonders are just a sample of what we saw in the Icelandic country side. We saw the Eyjafjallajökull volcano from a short distance, and herds of cattle and sheep at farms. Rural churches, more waterfalls and so much more

greeted us. Yet Reykjavik had many things for us to enjoy as well. It is a small city, with about 200,000 people living in it. Most buildings are low and no more than 2-4 stories high - reflective of the awareness of earthquake

activity in the area. The tallest building in Reykjavik is the stunning

Hallgrímskirkja

(left), a Lutheran church whose dramatic profile dominates the Reykjavik skyline. Some remark that it looks like a Space Shuttle, but it was designed in

the 1930s, long before the Space Shuttle was even an idea. Rather, its design is taken from massive basalt columns found in various parts of Iceland's natural landscape. Inside, it is dramatic in its simplicity, and we heard its 5000 pipe organ being played by

two of the church's organists - a thrill for sure. We also went to the top of the spire where the observation platform gave us dramatic views of the surrounding area - sea, mountains, houses, docks and so much more. We also visited

several museums that taught us a lot about Iceland, its land, culture and people.

And so it was, that after a week in Iceland, we boarded our Icelandair flight home to Boston. We left with so many wonderful impressions - first, of people we met, in particular our friend Oddur Björnsson and his family. They showed us many

kindnesses over the week and we look forward to seeing them again - either here in the United States or on a return visit to Iceland. We also left impressed with the remarkable natural landscape of a place very far away from us. Iceland has nothing

like the harsh winter and warm summers we are accustomed to - its climate is relatively moderate, with temperatures mostly in the 30-50 degree F range year round. But the landscape of Iceland is entirely volcanic - the island was born in the violence

of volcanic eruption and everywhere you look, you see evidence of this ongoing upheaval. We, who are accustomed to our modern conveniences like air travel, often get impatient when natural forces interrupt our plans. Being in Iceland, I got a

greater appreciation for the forces of nature, and how God has created a world of tremendous diversity, interest and ongoing excitement. That we are able to enjoy all of this is truly remarkable.

And so it was, that after a week in Iceland, we boarded our Icelandair flight home to Boston. We left with so many wonderful impressions - first, of people we met, in particular our friend Oddur Björnsson and his family. They showed us many

kindnesses over the week and we look forward to seeing them again - either here in the United States or on a return visit to Iceland. We also left impressed with the remarkable natural landscape of a place very far away from us. Iceland has nothing

like the harsh winter and warm summers we are accustomed to - its climate is relatively moderate, with temperatures mostly in the 30-50 degree F range year round. But the landscape of Iceland is entirely volcanic - the island was born in the violence

of volcanic eruption and everywhere you look, you see evidence of this ongoing upheaval. We, who are accustomed to our modern conveniences like air travel, often get impatient when natural forces interrupt our plans. Being in Iceland, I got a

greater appreciation for the forces of nature, and how God has created a world of tremendous diversity, interest and ongoing excitement. That we are able to enjoy all of this is truly remarkable.

Sunset over Reykjavik harbor, through the modern Viking ship sculpture, "The Sun Voyager", or "Sólfar" (right), provided a nice punctuation mark to our Icelandic journey. The calm of the water, a reminder of the ancient history of Iceland's people,

and the setting sun through clouds, all combined to create a memorable image. If you have not been to Iceland and you have the chance to visit, do not fail to do so. You will not be disappointed. Our week there gave us just a taste of the wonders

this beautiful country and its people have to offer, and my mind is full of images, thoughts and memories that will impact my artistic and life view for a long time to come.

August 17, 2011 - NEW

Today, I have announced my intention to retire from the Boston Symphony Orchestra on August 27, 2012, after over 27 years of service. For more information and the WHAT/WHY/WHEN of this important decision in my life, click

HERE to go to a new page on my website with more information.

July 11, 2011 - COMMENTARY

For my first year of undergraduate college, I attended Indiana University (1973-74). While I subsequently transferred from IU to Wheaton College (Illinois) where I graduated in 1976 and studied with Edward Kleinhammer, my year in the "Hoosier State" was very influential to my musical development.

While there, I studied trombone with Keith Brown. His is a name that is well known to any trombonist for his many editions of etudes, solos and orchestral excerpt books published by International Music.

For my first year of undergraduate college, I attended Indiana University (1973-74). While I subsequently transferred from IU to Wheaton College (Illinois) where I graduated in 1976 and studied with Edward Kleinhammer, my year in the "Hoosier State" was very influential to my musical development.

While there, I studied trombone with Keith Brown. His is a name that is well known to any trombonist for his many editions of etudes, solos and orchestral excerpt books published by International Music.

By an interesting coincidence, my two Boston Symphony trombone colleagues, Toby Oft and Steve Lange, also attended IU (although a generation later than me) and studied with Keith Brown. When I studied with Keith, he was in the third year of his

teaching tenure at IU - Steve graduated from IU in 1997 in what was Keith's final year of teaching. So all three trombone players in the Boston Symphony Orchestra can claim Keith Brown as one of our major influences.

This past weekend, Keith and his wife visited Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony, and saw our concert on Sunday afternoon that inlcuded Tchaikovsky's Symphony 6. Then yesterday, Steve, Toby and I celebrated Keith at a party

at our home (see photo, above). It was a fun, joyous occasion, where we all reminisced about our time at IU where Keith was not only a trombone teacher, but also one of the conductors of IU symphony orchestras. Toby and Steve both played Bartok's Miraculous Mandarin

under Keith's baton; I played Tchaikovsky Symphony 5 with him on the podium. Interestingly enough, the first time I met Keith Brown was when he was conductor of the "All Eastern Orchestra" in 1973. This group was made up of top high

school students from the northeastern states (Virginia and north) and we played a concert in Boston. Keith was the conductor of that group and it was at that point that I decided to attend Indiana University and study with him.

None of us is getting any younger, and I am at a point in life where it is important to seek out my teachers, mentors and others who have meant so much to me at different stages of my life. Keith Brown was one of those people whose life intersected

with mine and contributed to make me who I am today. That Toby, Steve and I all share a relationship with Keith is a special thing, and yesterday was a reminder of how important those relationships can be, even many years later.

June 30, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Now and then I have the opportunity to take part in an event that is nearly larger than life, and one that gives me both great pleasure and a lot to think about. Such was the case last week when I travelled to San Francisco to see

Richard Wagner's operatic tetralogy, "Der Ring des Nibelungen."

Now and then I have the opportunity to take part in an event that is nearly larger than life, and one that gives me both great pleasure and a lot to think about. Such was the case last week when I travelled to San Francisco to see

Richard Wagner's operatic tetralogy, "Der Ring des Nibelungen."

But first, a little back story...

Wagner's four interrelated operas, "Das Rheingold", "Die Walkure", "Siegfried" and "Gotterdammerung" are considered by many to be the greatest musical achievement of all time. While I might argue that Bach's "Saint Matthew Passion" would hold

that pride of place, there is no arguing that Wagner's "Ring" operas are an accomplishment like no other. The themes are iconic and known by anyone who has ever had a sense of musical culture. No synopsis can give it justice - if you know it, you

know it. If you don't, well, it's easy enough to read up on it. Gold in the Rhine river stolen by one who renounces love, forged into a ring of power, ring stolen by the head "god", the ring cursed, love, incest, marrying one's aunt, death, fire,

magic sword, magic potions, more death, a dragon, death again, more fire, world ends, gold returned to the Rhine river. Oh, and glorious music.

Wagner's four interrelated operas, "Das Rheingold", "Die Walkure", "Siegfried" and "Gotterdammerung" are considered by many to be the greatest musical achievement of all time. While I might argue that Bach's "Saint Matthew Passion" would hold

that pride of place, there is no arguing that Wagner's "Ring" operas are an accomplishment like no other. The themes are iconic and known by anyone who has ever had a sense of musical culture. No synopsis can give it justice - if you know it, you

know it. If you don't, well, it's easy enough to read up on it. Gold in the Rhine river stolen by one who renounces love, forged into a ring of power, ring stolen by the head "god", the ring cursed, love, incest, marrying one's aunt, death, fire,

magic sword, magic potions, more death, a dragon, death again, more fire, world ends, gold returned to the Rhine river. Oh, and glorious music.

For trombone players, the "Ring" contains some of the most exciting music we ever play. From the famous "Ride of the Walkure" to the dramatic soft chord underpinning of "Wotan's Farewell," playing Wagner's music is a joy. I have played two of

these operas, "Das Rheingold" and "Gotterdammerung" and selected acts and scenes of the others, both on bass trumpet and bass/contrabass trombones. Whether with Seiji Ozawa, Bernard Haitink or James Levine conducting, I have always enjoyed these

performances.

In 2005, my daughters, Linda and Robin, and I saw the "Ring" cycle with the Chicago Lyric Opera. We had such a good time with the whole experience that we decided to do it again this year. Robin is Communications Manager for

San Francisco Opera

and when she

told us that they would be doing the "Ring" this year, it didn't talke long for us to make plans to see it again, along with Robin's husband, John. My wife, who is not a great opera fan, decided to forgo 17 hours of Wagner for a few days of hiking

and biking in Maine's Acadia National Park with a friend. Everybody was happy.

In 2005, my daughters, Linda and Robin, and I saw the "Ring" cycle with the Chicago Lyric Opera. We had such a good time with the whole experience that we decided to do it again this year. Robin is Communications Manager for

San Francisco Opera

and when she

told us that they would be doing the "Ring" this year, it didn't talke long for us to make plans to see it again, along with Robin's husband, John. My wife, who is not a great opera fan, decided to forgo 17 hours of Wagner for a few days of hiking

and biking in Maine's Acadia National Park with a friend. Everybody was happy.

San Francisco is a beautiful city and I have visited there many times. It is not far from where I was born in Monterey, California, and getting back to the "left coast" always brings a new take on old memories. There is something about seeing the

Golden Gate Bridge (photo at above, right) that stirs in you something unique. We had beautiful weather for a week

(something on cannot take for granted in San Francisco, with its famous wet weather and foggy marine layer that rolls in from the Pacific Ocean). The four of us had two pairs of seats - one pair on the main floor and one pair in the first row of the

balcony. We took turns sitting together in each location in San Francisco's War Memorial Opera House. This way, we got two very different experiences with the music and staging.

Because Robin works in Public Relations for the SF Opera, we had a lot of inside information about the production. Robin has been managing a blog for the Opera, called

Notes from Valhalla. It contains interviews with many people associated with the production along with photos and other

interesting details. For instance, on the blog, we learned that the character Mime drinks a brand of beer that is the only kind he could possibly drink - Rheingold (photo at right, courtesy San Francisco Opera). We had a tour of backstage,

and had been talking about the production for months. With all of this information in hand, we set out to enjoy the production.

It is rare to see a "traditional" production of the "Ring" these days. Wagner's story and music can be read so many ways that directors today have seen the story in myriad ways. Director Francesca Zambella had an interesting concept: this was to

ben an "American Ring," set very much in the USA but over several different time frames. So we began in California during the gold rush of the 1840s with "Das Rheingold," moved to the World War II era for "Die Walkure" (complete with the Walkure

parachuting in as mid-century aviatrix), to the 1970s for "Siegfried," and into the future for "Gotterdammerung." While Zambella saw the gradual decrease of the power of the gods (brought about by the theft of the gold early in "Das Rheingold") as

an opportunity to make a point about environmental despoilation, the idea was anything but heavy-handed, and the deft use of projections and some superb props and scenery made the whole idea work well. The photo at left shows the moment in

Act III of "Siegfried" where Siegfried (Jay Hunter Morris) awakens the sleeping Brunnhilde (Nina Stemme) in one of the most famous moments in the tetrology - when Siegfried looks at Brunnhilde and says, "This is not a man!" (photo by Cory Weaver,

courtesy San Francisco Opera). The deep, moody atmosphere was very evocative.

It is rare to see a "traditional" production of the "Ring" these days. Wagner's story and music can be read so many ways that directors today have seen the story in myriad ways. Director Francesca Zambella had an interesting concept: this was to

ben an "American Ring," set very much in the USA but over several different time frames. So we began in California during the gold rush of the 1840s with "Das Rheingold," moved to the World War II era for "Die Walkure" (complete with the Walkure

parachuting in as mid-century aviatrix), to the 1970s for "Siegfried," and into the future for "Gotterdammerung." While Zambella saw the gradual decrease of the power of the gods (brought about by the theft of the gold early in "Das Rheingold") as

an opportunity to make a point about environmental despoilation, the idea was anything but heavy-handed, and the deft use of projections and some superb props and scenery made the whole idea work well. The photo at left shows the moment in

Act III of "Siegfried" where Siegfried (Jay Hunter Morris) awakens the sleeping Brunnhilde (Nina Stemme) in one of the most famous moments in the tetrology - when Siegfried looks at Brunnhilde and says, "This is not a man!" (photo by Cory Weaver,

courtesy San Francisco Opera). The deep, moody atmosphere was very evocative.

As the operas went on - as I mentioned, there is 17 hours of opera to see in this mammoth undertaking - we enjoyed taking in the whole experience which included watching people at intermission, and of course talking about what we had seen,

arguing and agreeing about how various scenes worked, how the orchestra sounded and comparing the experience to when we saw the "Ring" in 2005 in Chicago. Never mind that Wagner's storytelling sometimes leaves a lot to be desired - there are

plenty of things that just don't add up or make sense. They provided opportunities for more conversations as we shared what we saw and thought. We also continued a tradition we started in 2005 - each night, we had a photo taken of

the four of us while we held up fingers that told what opera we were seeing that night. The photo at right shows (left to right) me, Robin, John and Linda outside the Press Room at War Memorial Opera House. With our holding up three fingers, you

know that we were enjoying "Siegfried." You will see I'm holding a copy of the "Ring" program, with the stunning cover image (also made into a poster) by Michael Schwab (see a larger image of this cover at the beginning of this entry).

It shows Brunnhilde in her aviatrix outfit, surrounded by flames, standing in

the Rhine River, with a bit of a vine beginning to grow again in the midst of the conflagration. Hope.

As the operas went on - as I mentioned, there is 17 hours of opera to see in this mammoth undertaking - we enjoyed taking in the whole experience which included watching people at intermission, and of course talking about what we had seen,

arguing and agreeing about how various scenes worked, how the orchestra sounded and comparing the experience to when we saw the "Ring" in 2005 in Chicago. Never mind that Wagner's storytelling sometimes leaves a lot to be desired - there are

plenty of things that just don't add up or make sense. They provided opportunities for more conversations as we shared what we saw and thought. We also continued a tradition we started in 2005 - each night, we had a photo taken of

the four of us while we held up fingers that told what opera we were seeing that night. The photo at right shows (left to right) me, Robin, John and Linda outside the Press Room at War Memorial Opera House. With our holding up three fingers, you

know that we were enjoying "Siegfried." You will see I'm holding a copy of the "Ring" program, with the stunning cover image (also made into a poster) by Michael Schwab (see a larger image of this cover at the beginning of this entry).

It shows Brunnhilde in her aviatrix outfit, surrounded by flames, standing in

the Rhine River, with a bit of a vine beginning to grow again in the midst of the conflagration. Hope.

The themes of the "Ring" speak differently to each person. For me, I was impressed once again with the fact that there are no heroes. Eveyrone is a scoundrel. They disobey orders, violate vows, murder, steal, lie. All of them. There is no

righteous person among the princpals in the cast. These operas always give me a lot to think about when considering how we live in our post-modern world, where the old themes of mythology (that is the basis of Wagner's story) continue through today and beyond,

told a little differently, but always with us. How I order my own life in light of "the way everyone does things" is an important part of how I consider my own actions in light of my own world-view.

And there was more fun to have. We took a trip to Muir Woods north of San Francisco, walking through a grove of giant redwood trees. Even on a busy Saturday amidst many other people, we could still get lost a bit in the beauty of the surroundings,

and the unique landscape that was before us. Linda and I went to a beach and put our feet in the Pacific Ocean; later we wet to the California Academy of Sciences ad other museums. We enjoyed some great food - from Robin's fine cooking (ably assisted by Linda), Mexican, and Japanese (at "sushi-boat" where plates of sushi float by on little boats ready for you to choose and then

pick what you want). We even had some fun with some traditional Walkure helmets that Robin had in her office (photo at left).

And there was more fun to have. We took a trip to Muir Woods north of San Francisco, walking through a grove of giant redwood trees. Even on a busy Saturday amidst many other people, we could still get lost a bit in the beauty of the surroundings,

and the unique landscape that was before us. Linda and I went to a beach and put our feet in the Pacific Ocean; later we wet to the California Academy of Sciences ad other museums. We enjoyed some great food - from Robin's fine cooking (ably assisted by Linda), Mexican, and Japanese (at "sushi-boat" where plates of sushi float by on little boats ready for you to choose and then

pick what you want). We even had some fun with some traditional Walkure helmets that Robin had in her office (photo at left).

We saw what was the second of three weeks of San Francisco Opera's "Ring" production. As a father, I was so happy to see Robin in action at work - I am very proud of my children and to be together with all of them for a week made for a great

time. This week, Robin has an additional duty - she is calling the "supertitles" that are projected over the stage during the performances. Supertitles are a variation of movie subtitles. Wagner's operas are sung in German, so to make

the action more understandable for non-native German speakers, translations in English of many lines from the operas are projected on a screen. This is not as obtrusive as you might think, and is a great aid to enjoying the production. This week,

Robin is in a booth with a score to each opera and it is she that determines when each supertitle slide is projected. In this, she has a unique view of the action and by the end of the week, she will know the "Ring" as well as anyone I know -

including me!

When it was over, and we celebrated with a great meal at "sushi boat" and headed home. Linda flew back to Chicago and I came back home to Boston. The week was joyful and exhausting. These operas are LONG, and even with an early starting time,

we didn't get to sleep until after 1 am on several nights. The emotional energy of considering Wagner's themes, and the sheer beauty of the music took a lot out of us. And there is much more to keep thinking about and talking about. In this

week of shared experience with my daughters and son in law, we laid another brick on the foundation of our lives, with something to share together over and over. We each turn to "the next thing" in our busy lives, but are so happy to have

shared this moment in time together. Some may think it's a strange thing to do, but when I got home, I promptly put one of my many recordings of the "Ring" cycle in my car, and I will spend my time commuting this summer listening once again to

the "Ring." After 17 hours of this music, I want to listen to it all again. And when I get to sit on stage with a trombone in my hand and play it again myself, it will have an even deeper meaning for the experience I had last week at San Francisco Opera.

June 12, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Because of my interest in a wide variety of things, my life is full of interesting juxtopositions that pull me from one world to another. This past week was one of rich experiences, all very different and all very exciting.

Because of my interest in a wide variety of things, my life is full of interesting juxtopositions that pull me from one world to another. This past week was one of rich experiences, all very different and all very exciting.

You have read, in the entry below, of my three performances as soloist with the Boston Pops Orchestra in the finale of Chris Brubeck's Concerto for Bass Trombone, James Brown in the Twilight Zone. This

jazzy, funky piece is a thrill for me to play and it takes me outside my primary performing world of sitting in the back row of a symphony orchestra playing the great classical music of the last two centuries.

But yesterday, I found myself in two more different worlds - at Yale University giving a talk and presentation about the serpent at the Hardy at Yale II Conference of the

Thomas Hardy Association.

Thomas Hardy was an English writer of the late

19th and early 20th century. He wrote often about 19th century rural English country life and music was a big part of that time and place. In eleven of his works, he mentions the serpent, and I was very honored to be asked to give a presentation

on Hardy and the serpent at the Association's Conference at Yale University. In conjunction with my presentation, I wrote an article, "A Good Old Note: The Serpent in Thomas Hardy's World and Works" that has been published in the current issue of

the Association's Journal, The Hardy Review.

My presentation was held at the

Yale Collection of Musical Instruments.

That setting was ideal for the event because Yale has three serpents in the Collection that figured into my talk. I also played two of my serpents: my c. 1812 French church serpent in

C by Baudouin (which I am playing in the photo, above) and my 2007 English military serpent by Keith Rogers, after an example by Francis Pretty. My presentation concluded with a very nice reception where I enjoyed talking with many of the Hardy

scholars who were taking part in the conference. This was a very international crowd, and the proliferation of accents made me feel like I was at the United Nations. It was a vibrant, interesting group of people with whom I enjoyed sharing

nice conversation, and I offer my particular thanks to Rosemarie Morgan, President of the Thomas Hardy Association, and Susan Thompson, Curator of the Yale Collection of Musical Instruments who did so much to make my time at Yale so enjoyable.

The Boston Pops. A concerto performance. A meeting with a book publisher. Yale University. The serpent. Thomas Hardy. An intersection of worlds and centuries in the span of a week, all having to do with music. As I reflect today on the

events of the last few days, I have to smile at this tremendous juxtoposition, and how music binds together people across cultures and years.

June 8, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Most of my work as a performing musician is done in community. Whether playing bass trombone, serpent or ophicleide, it is playing in an ensemble with other musicians that not only represents the primary amount of time I spend on stage, but

it is also the thing I do and like the best about playing my instruments. The instruments I play were conceived to play in groups rather than as solo instruments. The bass trombone has a particular role to play in the symphony orchestra,

jazz band or concert band, and I relish the challenges of working with colleagues to produce the best possible section sound, blend and ensemble in our supporting role.

Most of my work as a performing musician is done in community. Whether playing bass trombone, serpent or ophicleide, it is playing in an ensemble with other musicians that not only represents the primary amount of time I spend on stage, but

it is also the thing I do and like the best about playing my instruments. The instruments I play were conceived to play in groups rather than as solo instruments. The bass trombone has a particular role to play in the symphony orchestra,

jazz band or concert band, and I relish the challenges of working with colleagues to produce the best possible section sound, blend and ensemble in our supporting role.

Yet, from time to time, I have the opportunity to take a step forward out of the back row of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and stand up front next to the conductor and play a solo. For a bass trombonist, the opportunities are fewer than for other

instruments, particularly because we lack the substantial solo repertoire like violin, flute or even trumpet. In my career, I'm been fortunate to be soloist with dozens of ensembles, and last night was one of those occasions, where I played the

finale of

Christopher Brubeck's

Concerto for Bass Trombone, James Brown in the Twilight Zone, accompanied by the Boston Pops Orchestra, Keith Lockhart, conductor. It was simply a thrill to play Chris' piece once again and

enjoy having my BSO colleagues offering such an expert and supportive accompaniment to me.

Chris Brubeck - yes, in answer to the inevitable question, he is the son of jazz great Dave Brubeck - and I met in the late 90s, when he and the late Bill Crofut were giving a "family concert" with the BSO at Symphony Hall. Chris and I met up

at intermission. I had known he played bass trombone but was unprepared for his telling me that he had just completed a bass trombone Concerto. Our conversation immediately turned to my question, "When can I get a copy?!" and within a few days,

I had in my hand what I consider to be one of the finest pieces ever written for bass trombone solo. In time, I had discussions with Keith Lockhart, conductor of the Boston Pops, and I played Chris' Concerto with the Boston Pops (I also

played it that same year at the International Trombone Festival in Potsdam, New York), and subsequently

played the piece's finale on the television show, "Evening at Pops." A few years ago, I performed Chris' second bass trombone Concerto, the Prague Concerto with Gerald Steichen conducting the Boston Pops and I was honored when

Chris asked me to edit the piece for publication by Carl Fischer.

Chris Brubeck - yes, in answer to the inevitable question, he is the son of jazz great Dave Brubeck - and I met in the late 90s, when he and the late Bill Crofut were giving a "family concert" with the BSO at Symphony Hall. Chris and I met up

at intermission. I had known he played bass trombone but was unprepared for his telling me that he had just completed a bass trombone Concerto. Our conversation immediately turned to my question, "When can I get a copy?!" and within a few days,

I had in my hand what I consider to be one of the finest pieces ever written for bass trombone solo. In time, I had discussions with Keith Lockhart, conductor of the Boston Pops, and I played Chris' Concerto with the Boston Pops (I also

played it that same year at the International Trombone Festival in Potsdam, New York), and subsequently

played the piece's finale on the television show, "Evening at Pops." A few years ago, I performed Chris' second bass trombone Concerto, the Prague Concerto with Gerald Steichen conducting the Boston Pops and I was honored when

Chris asked me to edit the piece for publication by Carl Fischer.

Last night's performance - and there are two more, on Thursday and Friday of this week - was made all the more special because Chris and his wife, Tish, were in attendance. Along with my wife, Patricia, and our friends Steve and Nancy Gerber, Chris

and Tish sat at a table on Symphony Hall's main floor. I knew he was there, and there is something very unique about playing a piece when you know the composer is in attendance. Chris had heard me play his piece previously, but I had some new

things to bring to it last night. It was nice to be able to recognize Chris after my performance was done, and see him take a bow in the spotlight while an appreciative audience gave him his due. The photo above (right), taken by my

friend Michael J. Lutch, shows me during the performance, with conductor Keith Lockhart on the podium.

The photo above (left), taken by my BSO trombone colleague Steve Lange, shows Chris and me at intermission last night, after my performance, in the soloist's dressing room at Symphony Hall. I think our faces tell the story: I was pleased with the performance and so was Chris. Even more important to me was that it was an opportunity to see this

good friend of mine again, and enjoy being together in celebration of his great music. After intermission, I joined Chris, Tish, Pat and our friends in the audience to hear the rest of the concert - a rare thing for me since I am usually on stage

performing rather than listening in the audience. It was a memorable night of music, friendship and myriad happy thoughts. And while I am enjoying this week of solo performances, I will enjoy - just as much - getting back to my usual seat in the

back row of the orchestra next week for the final week of the Boston Pops season, a season that has seen me begin my 27th season as the bass trombonist of the Boston Symphony.

May 12, 2011 - NEW

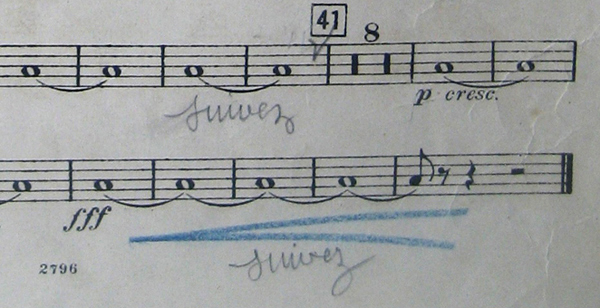

For generations, the 60 Etudes, Opus 6 by Koppraasch have been an important part of trombone teaching and learning. Originally for low horn, these Etudes have been in print over the years with many publishers. In 2000, I became aware that

Kopprasch wrote another book of Etudes, his Opus 5. Originally for high horn, these etudes are, to me, more musically interesting than the well known Opus 6 Etudes. My friend, trombonist and scholar Benny Sluchin,

prepared an edition of the Opus 5 Etudes in 2000. Over the years, I have thought it would be useful to have an edition of those Etudes an octave lower so they would be suitable for bass trombone. At my request, Benny has

graciously agreed to create the new edition of the Kopprasch Opus 5 Etudes for bass trombone. But not only that, he has decided to give away this edition free of charge as a PDF download. Benny asked if I would be willing to host the

download on my website and I was happy to agree. So, beginning today, players and teachers can download Benny Sluchin's edition for bass trombone of the Kopprasch 60 Etudes, Opus 5. Click

HERE

to go to the Kopprasch download page on my website. And once you do, get back to practicing!

March 5, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Not to be lost in this week's news of the resignation of James Levine as music director of the Boston Symphony is the fact that we continue to play concerts at Symphony Hall and make plans

for upcoming concerts in Carnegie Hall, Newark and Washington D.C. The show, as they say, goes on.

Not to be lost in this week's news of the resignation of James Levine as music director of the Boston Symphony is the fact that we continue to play concerts at Symphony Hall and make plans

for upcoming concerts in Carnegie Hall, Newark and Washington D.C. The show, as they say, goes on.

This week the Boston Symphony is premiering a new violin concerto by British composer Harrison Birtwistle, an event that has a nice intersection for me with my long time involvement in the

British brass band movement.

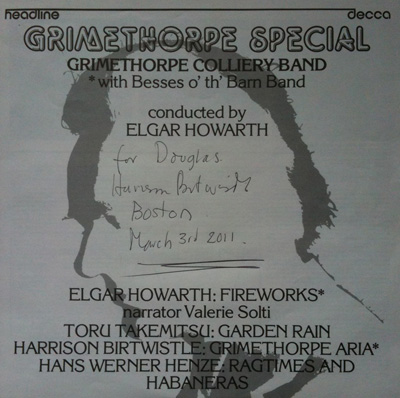

Sir Harrison Birtwistle has been known to me for many years not for his considerable output as a composer for symphony orchestra, but for a work he wrote in 1973 for brass band. His

Grimethorpe Aria, commissioned by the

Grimethorpe Colliery Band,

was released in 1976 on a Decca LP (Decca HEAD 14), Grimethorpe Special (see photo, right, with

Birtwistle's inscription to me on the accompanying liner notes). It is one of a handful of brass band recordings that has been released on a major label and

some have called it "one of the most important brass band recordings ever made." I tend to agree.

The LP contains three works for brass band in addition to Birtwistle's contribution: Elgar Howarth's Fireworks (with Lady Valerie Solti, narrator), Toru Takemitsu's,

Garden Path and Hans Werner Henze's Ragtimes and Habaneras. Each work is certainly what you would call, "contemporary music." But to my ears, today - after my long career of playing new music - none of the works sound

especially challenging to listen to. But in 1976 - when the non-Salvation Army brass band movement

was still playing classical transcriptions as the bread-and-butter of their repertoire, Grimethorpe Special took brass banding by storm. It opened up an important

discussion about the role of the brass band in the contemporary music conversation, and shook up the "old guard" in a dramatic way. Conductor Elgar Howarth was at the forefront of the

brass band's charge into modernity and his advocacy certainly paid off; today, brass band repertoire is truly on the cutting edge, with major composers writing for the medium and contests

and concerts

full of works that are aurally challenging and musically satisfying.

At a Boston Symphony rehearsal earlier this week, I enjoyed a nice conversation with Birtwistle about his Grimethorpe Aria. He seemed pleased to see I had a copy of my now nearly

40 year old recording of his piece (it remains a rare recording and, unfortunately, has not been released on CD), and was more than happy to sign my copy. On Thursday night, he asked the brass

to stand for a bow at the end of the piece (see photo above, left, by Michael J. Lutch -

Birtwistle is in the front of the orchestra standing (grey hair); violinist Christian Tetzlaff is standing at left, conductor Marcelo Lehninger is seen gesturing to the brass section of

two trumpets, two trombones and tuba - Michael Martin, Thomas Siders, Toby Oft, myself and Mike Roylance).

It is always nice to see connections between diverse parts of my musical life. I had never played any music written by Birtwistle before this week, yet I have known of his music - through

his sole work for brass band - for many years. To have a conversation with him about his writing for brass band at the same time we were playing his newest piece for symphony orchestra

reminded me again of how the musical world is deeply interconnected.

March 3, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Change usually comes slowly to the Boston Symphony Orchestra but in the last week, it has been occuring at a breakneck pace, culminating with the announcement during rehearsal yesterday

afternoon that James Levine, the 14th Music Director of the BSO, would be stepping down from that role at the end of the summer, and that he would not be conducting us

for the rest of this season.

Change usually comes slowly to the Boston Symphony Orchestra but in the last week, it has been occuring at a breakneck pace, culminating with the announcement during rehearsal yesterday

afternoon that James Levine, the 14th Music Director of the BSO, would be stepping down from that role at the end of the summer, and that he would not be conducting us

for the rest of this season.

When Managing Director Mark Volpe made the announcement, it was greeted with stunned silence by the orchestra, although a sense of inevitablilty had set in during recent days. James Levine is

a tremendous musician, but in the past few years, various health issues - a torn rotator cuff, a cancerous kidney, several back surgeries - have caused him to miss more and more concerts with the

Orchestra. After rehearsing Mahler's Symphony 9 last week and then pulling out of the concerts, citing problems with pain and the medications to manage it, he and the BSO mutually

agreed it was time to part ways in order to allow Jimmy (as we call him) to get his health in order and for the BSO to begin the process of looking for a new music director.

When Managing Director Mark Volpe made the announcement, it was greeted with stunned silence by the orchestra, although a sense of inevitablilty had set in during recent days. James Levine is

a tremendous musician, but in the past few years, various health issues - a torn rotator cuff, a cancerous kidney, several back surgeries - have caused him to miss more and more concerts with the

Orchestra. After rehearsing Mahler's Symphony 9 last week and then pulling out of the concerts, citing problems with pain and the medications to manage it, he and the BSO mutually

agreed it was time to part ways in order to allow Jimmy (as we call him) to get his health in order and for the BSO to begin the process of looking for a new music director.

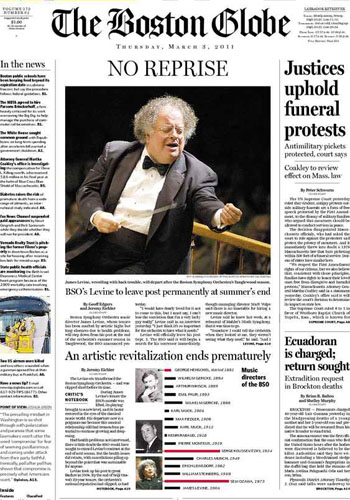

Today's Boston Globe headline screamed the story on page one - we are used to reading reviews deep in the "Arts" section, not reading news about the orchestra above the first page fold.

But this is big news. The BSO is Boston's premiere cultural institution, an engine that drives a strong arts economy and filters down to many other organizations. This is true not only in Boston,

but in New York, at our summer festival home at Tanglewood in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts, and world-wide when on tour.

I was hired by the BSO in 1985 by then-music director Seiji Ozawa. His 29 year tenure as music director was unprecedented in BSO history. Levine's tenure was short by comparison - only

seven years. There were many great concerts along the way - our performances of Berlioz's Les Troyens and Damnation of Faust (on which I played ophicleide - the

photo above by Michael J. Lutch - right - shows me talking with Jim after a sound check preceeding our performance of Faust in Paris in 2007) immediately stand

out among the artistic highlights of my career. But, as Woody Allen famously said, "Showing up is 90% of the job." With Jimmy's many absences, it has been frustrating to deal with

late changes in conductor and programming, and nobody bears that burden of last-minute change greater than the orchestra itself.

All of us in the BSO wish Jimmy the very best for his future, and we hope he is able to address his myriad health issues and once again come back to conduct the Orchestra as a guest

conductor or in some yet to be defined titled role. I am immensely

grateful for having had the opportunity to play under his baton and to have many conversations with him about music. The BSO made several recordings under his leadership - including

Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe that won a 2009 Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance - and had a very rewarding tour of Europe in 2007. It was under his watch that the two

new members of the BSO trombone section - Toby Oft and Steve Lange - were hired, and the orchestra has achieved a level of playing that is immensely satisfying. Change is in the air

at Symphony Hall, and in the coming months, we will see a parade of guest conductors where the question will be, each time, "Is this the ONE?" I have confidence in our selection

process, in the Player members of the search committee and in the BSO Board of Trustees. In the meantime, you will see me in my usual chair on stage, playing the best I can for

whoever is on the podium, and waiting, like everyone else, for this transition to play out and for the BSO to hire its 15th Music Director.

January 28, 2011 - COMMENTARY

This month has been full of a lot of news - hence the frequent updates to this page. One theme that has been dominant has been near record level snowfall in the Boston area. It's just

one of those years. I've seen a lot of snow in my lifetime. My wife and I lived in New York City for the "Blizzard of 1978" that shut down the whole Northeast for days. In 1997,

I gave a recital in Boston's Jordan Hall on April Fool's Day eve as three feet of snow began to fall in less than 24 hours.

And in 1995, I was in Boston for the record snowfall for a winter -

107.6 inches.

This month has been full of a lot of news - hence the frequent updates to this page. One theme that has been dominant has been near record level snowfall in the Boston area. It's just

one of those years. I've seen a lot of snow in my lifetime. My wife and I lived in New York City for the "Blizzard of 1978" that shut down the whole Northeast for days. In 1997,

I gave a recital in Boston's Jordan Hall on April Fool's Day eve as three feet of snow began to fall in less than 24 hours.

And in 1995, I was in Boston for the record snowfall for a winter -

107.6 inches.

This year is on pace to break the 1995 record. With at least two more months of snow-dumping winter ahead of us, we're already up to over 60 inches of snow. Roads are narrow with piles upon

piles of snow on either side. Our front walkway and driveway look more like trenches than paths. My mailbox is buried in a huge pile of snow at the end of my driveway, invisible

from our house. Yes, I have a great Toro snowblower, but it still takes two-three hours to clear my driveway after a major snowfall - like the 12" that got dumped on us yesterday.

Relentless snow and its cleanup - and the challenge of driving in it (and dealing with other drivers who sometime seem oblivious to the added caution needed when you can't see around

corners due to massive mountains of snow as well as slippery road conditions) - be getting a little numbing.

So it was particularly welcome to see this humorous graphic in

today's Boston Globe. Shaquille O'Neal is a giant of a man, and

a beloved member of the Boston Celtics basketball team. You may recall seeing the commentary and video of his debut as conductor with the Boston Pops that I posted to my "What's New?"

page last month - you can see that by clicking

HERE and going to the entry for December 21. Putting the snow in this perspective made me smile - the first

smile to cross my face when thinking about the subject of snow in a very long time.

And, on a completely unrelated note, I have another reason to smile. Yesterday, my Boston Symphony Orchestra second trombone colleague, Steve Lange, received tenure in the BSO. We now have

a full, tenured trombone section for the first time in three years. This is happy news for all of us in the Boston Symphony. Steve, along with Toby Oft (principal trombone) and I are enjoying

a rare time of very satisfying collaboration. I do not take this for granted since it is not always easy to blend distinct personalities into a cohesive section. That we are doing this

is a great joy and is providing me - at this point in my nearly 30 year career as a professional orchestral bass trombonist - with much for which to be thankful. Snow, Shaq and Steve. "S"

is running wild right now in my little universe. Good reason to smile.

Until the snow starts falling again...

NB: The graphic of snowfall in Boston was updated on May 18, 2011. We didn't break the snowfall record - we actually didn't get close - but there was no complaint from me...

January 26, 2011 - UPDATE

I have updated my

schedule page

with details of my upcoming solo performances with the Boston Pops Orchestra in the finale of Christopher Brubeck's Bass Trombone Concerto, "James Brown in the Twilight

Zone" and my presentation at Yale University at the Thomas Hardy Association's "Hardy at Yale II" Conference.

January 24, 2011 - COMMENTARY

Today I took part in a recording session for a new production for the Boston Museum of Science Planetarium,

Undiscovered Worlds: The Search Beyond Our Sun. During my career, I have taken part in hundreds of recording sessions,

whether for commercial studio groups in New York City, the Baltimore or Boston Symphony Orchestras, the Boston Pops Orchestra, the New England Brass Band or my own solo recordings. Recording is a fascinating process and no matter