|

|

15. I've been experiencing pain in my left arm when playing trombone. What is causing it and how can I fix the problem?

The popular slogan says "No pain, no gain" but those are surely words only a fool could take to heart. The fact is that pain is often a signal from our body that something is quite wrong, and putting up with pain - "toughing it out" - can often cause permanent damage. Recognizing pain when it occurs and working to eliminate it can help ensure not only comfort while playing but a long, pain-free career as well.

Players often ask me why they are experiencing pain while playing. Such pain usually occurs in the left or right hand, elbow or shoulder. Some people have reported serious injuries that include torn shoulder muscles while others speak of a sharp or dull ache that persists even when not playing.

The first thing I recommend a person do is to analyze whether the pain is being caused by playing trombone or by something else. For instance, in our computer age, many people suffer from a "Repetitive Stress Syndrome" from using the computer keyboard. The right hand and arm are particularly vulnerable. Consider the use of your right "pinky" finger which has responsibility for two of the most frequently keys on the computer - the "delete" and "return" keys as well as the mouse or trackball. People who spend hours a day using a computer can cause tension in their hands and arms that will then telegraph to other parts of the body as well. Creating a more user friendly work environment will help with such strain.

It may very well be that you are suffering from tendonitis. This is not an uncommon condition (which results from a minor tear of the tendons of the elbow - it is often known as "tennis elbow" although the majority of people who suffer from it do not get it from playing tennis). There are many successful treatments for tendonitis but ignoring it is not one of them. Consult your doctor or physical therapist if ANY kind of chronic pain persists.

I remember going into a lesson many years ago with my teacher, Edward Kleinhammer (retired bass trombonist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra) one day and finding him sitting in his chair, with his trombone in the resting position, staring blankly ahead. I circled him (he was acting like a "Bobby" in front of Buckingham Palace - utterly motionless) and after a few minutes I asked him, "What are you doing?!" "Relaxing my nose," was the reply. Mr. Kleinhammer was going through a complete body inventory of relaxation. Why? Because he struggled with tension every day. From him I learned that we actually need to think about this, not just assume that when we pick up a trombone all will be well. For many people, holding the trombone is so unnatural that they develop curious and harmful mechanisms to cope with it. Simply realizing that there is tension and working to reduce it is a good first step.

The trend towards heavier and heavier equipment is also exacting its toll - particularly bass trombones, now with various generations of Thayer valves, heavy valve caps, double valves and very heavy bells - these instruments are increasingly less "balanced" requiring more phyusical support from the player. The "balance" point of a bass trombone is NOT where the left hand holds it. Recognizing this is important.

How we sit is important as well. It's a well known medical fact that if we swing our arms naturally from front to back, the arms to not go back and forth (front to back) in exact parallel. In fact, the hands will eventually "clap" behind your back. Davis Shuman knew this when he developed his so called "angular trombone" with Martin in the 1960's. The hand slide actually went out at an angle of about 12 degrees to the right, more closely letting the right arm move at its natural angle. Trying to force the trombone slide to move straight out from the body is unnatural and can lead to stress. I solve this by positioning my chair at an angle (turned slightly to the left of center), turning my head slightly to the right and then allowing my arm to operate in a natural position (this also has the advantage of giveing you .5 - 1 inch of additional "reach" with the slide).

What we sit on is also important. Chair manufacturers seem to be utterly out of touch with reality, even those who allegedly design chairs for concert hall stage use. Soft, squishy bottoms, scooped bottoms, high legs and all the rest contribute to back strain which immediately goes to shoulders, elbows and the rest. A whole industry of music medicine is growing and there even is a journal devoted to this subject alone.

Remember that EVERY stock trombone was designed with SOMEONE in mind as the prototypical model. But NOBODY is exactly like you. For instance, it is absolutely beyond my range of comprehension to imagine who the Edwards trombone company had in mind when designing the placement of their double valve triggers. You must have a HUGE hand to have any degree of comfort. When I hold an Edwards double valve bass, my hand freezes in less than a minute. You MUST make modifications so it fits YOU. My Yamaha YBL-822G paddles are designed for ME, so that's how they made it - but anyone else will probably need to modify them in some way (this is true for EVERY horn) - even with the adjustable paddles that come on many horns you may need to see a repairman to make adjustments. If you don't do this you will suffer greatly. This is a small monetary investment to save a great deal of grief.

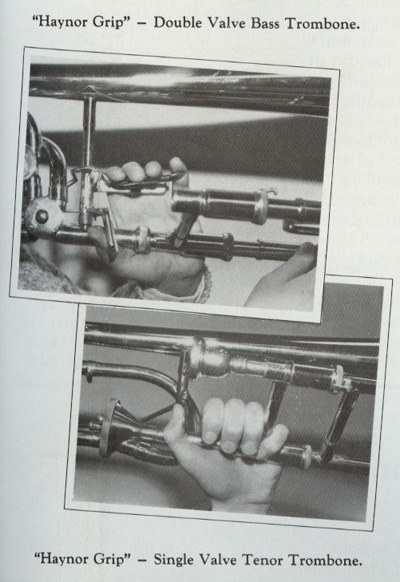

The left hand grip is critical. The photos below will help in explaining how I hold my trombone. For the sake of clarity, I number the fingers 1 - 5, with the thumb being 1, the index finger, 2, your pinky being 5 and so on. Most players (both tenor and bass) play trombone with finger 2 on the mouthpiece and fingers 3-5 jammed under the slide brace like this:

This is the way everyone seems to be taught and most people do so because they've never tried anything else. There's only one problem - it causes many people extreme left hand fatigue which then telegraphs to the left elbow and shoulder.

Hold your horn and walk through this with me.

Notice how with 3 fingers under the slide brace you have a stretched "web" of skin between fingers 2 and 3? How there is a relatively long distance from your thumb to finger 2 on the mouthpiece? How finger 3 feels "squashed" (especially if you're trying to operate a bass trombone second valve with the same finger).

The solution is simple - put the slide brace between fingers 3 and 4 like this:

You will notice an immediate reduction of tension. Finger 2 (on the mouthpiece) is now closer to the thumb. The webbing between fingers 2 & 3 is natural and relaxed. Finger 3 loosly wraps on the receiver (no apparant function unless you play a bass trombone second trigger in which case you have a finger blissfully free of being squashed). Fingers 4 & 5 are comfortable (and with ony two fingers after the slide brace instead of three, you'll probably never again pinch your hand when bringing the slide in quickly - ouch!).

The net effect of all this is to move your hand one finger (about 1 inch) closer to the thumb (bell brace) giving the hand a much more natural position without stressful stretching.

Yes, it will feel unusual, but after a few days, you will be used to it. If you play bass trombone, you may need to have your second valve paddle moved to a different position so you can easily reach it, but I assure you, the benefits will be immediate.

Try it. It just may be the solution you've been looking for.

Remember the old story about the doctor and patient:

A guy goes into the doctor's office, raises his right arm, says "Doc, it hurts when I do this."

The Doctor replies..."Don't DO that !!!"

While most people are aware of the benefits of aerobic exercise (20 minutes of walking, running, cross country skiing, using a non-motorized treadmill or Nordic Trak ski exerciser, 3-5 times a week, in order to improve cardio-vascular fitness), there is another form of exercise which is often overlooked which can be of immense benefit to trombonists.

Stretching.

By this I am not talking about weight training for building muscles, but I am

speaking of stretching in order to keep muscles limber and flexible, and to

reduce tension. Most people have no real idea of how to "stretch" and I have

found in my own experience that spending 10-15 minutes a day doing some simple

stretching exercises can help legs, arms, shoulders and the neck and reduce

overall body tension significantly. The benefit to playing the trombone is immense.

By this I am not talking about weight training for building muscles, but I am

speaking of stretching in order to keep muscles limber and flexible, and to

reduce tension. Most people have no real idea of how to "stretch" and I have

found in my own experience that spending 10-15 minutes a day doing some simple

stretching exercises can help legs, arms, shoulders and the neck and reduce

overall body tension significantly. The benefit to playing the trombone is immense.

The best resouce for learning a helpful and manageable stretching regimen is Bob Anderson's fine book Stretching (Shelter Publications, 2000 [20th Anniversary revised edition], ISBN 0-936070-22-6 - paperback). It is widely available in bookstores including the online book resource, amazon.com.

Bob Anderson has also written a companion book, Stretching at Your Computer or Desk (Shelter Publications, 1997, ISBN 0-679-77084-4 - paperback) which includes exercises you can do while sitting in your chair while practicing, in rehearsal or concert. It can also be found at amazon.com.

I use the exercises in these books regularly and highly recommend the insights and exercises contained in Bob Anderson's fine resources.

Relax, stop suffering, stop wincing when you play, enjoy playing the trombone, get off the beta-blockers, take a deep breath - remember we need to ENJOY the trombone. Pain is reflective of tension which is often reflective of stress and/or anxiety. Our playing will always reflect the pain. Forget the fool who coined the "No pain, no gain" phrase. He's in the hospital and he didn't win the audition....

There are other modifications and adjustments which have been developed by various technicians and manufacturers in order to help reduce left hand and body tension.

John Haynor, a bass trombonist and instrument repairman in the Chicago area developed the "Haynor grip" (after an idea his college friend, trombonist Bill Chandler, showed him) which is designed to take tension off of the left hand. The Haynor grip is a modification which can be made by a competent repairman; it is common enough that many technicians have developed their own variation on this grip.

The photos below show two Haynor grip configurations. These photos were taken by me in 1985 and appeared in an article I wrote for The Instrumentalist magazine (November 1985, Volume 40, Number 4, pages22-28) titled, "The Bass Trombone: Innovations on a Misunderstood Instrument."

The top photo shows bass trombonist Carol Bruner Swinchoski who at the time the photo was taken in 1985 was a student at the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore. The basic premise behind the Haynor grip is to have the horn rest on the butt of the hand and avoid the stretch of the left index finger which is required with a standard grip. With the Haynor grip, a new brace is added to the horn around which the left hand fingers curl. In this photo of a bass trombone Haynor grip, fingers 2, 3, and 4 curl over a new brace which extends from the main bell brace while the same fingers activate the second trigger paddle. Note how the f-attachment trigger now is on the other side of the slide receiver.

The second photo shows tenor trombonist Eric Carlson, currently second trombonist of the Philadelphia Orchestra (when the photo was taken in 1985 he was playing in the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra). The principle in this Haynor modification is the same as on the bass trombone above except without a second trigger to operate, the new brace extends from the hand slide brace and fingers 2, 3, and 4 (which in the photo above are covering the new brace which extends from the hand slide) go around the new brace while finger 5 goes around the upper hand slide brace. The Haynor grip is a useful configuration, particularly for trombonists with small hands.

Sometimes you have to hold an instrument that just won't sit correctly on your left hand. I have no trouble holding the bass trombone, but bass sackbut is another story. The bass sackbut is pitched in F and therefore is quite long. In order to reach the outer positions, the bass sackbut is equipped with a handle attached to the hand slide - you hold the handle rather than a brace on the hand slide with you play the bass sackbut. Because of this, the instrument is very "front heavy." In addition, reproductions of historical sackbuts often hav flat 'stays" rather than round braces and the "stay" on the bell is often too far away for your thumb to reach comfortably.

I encountered this problem when I was playing bass sackbut in performances of the Monteverdi Vespers with Boston's Handel and Haydn Society. I was using a bass sackbut by Frank Tomes (London) which was not easy to hold. The solution I came across was suggested to me by my friend Robert Couture (who played alto and tenor sackbut in the Vespers performances). I purchased a hand strap made by Yamaha (Yamaha product number YAC-1535P) which wraps first around the mouthpiece, then around the bottom of the hand grip, and then around my left hand. This way, the weight of the sackbut was on the fat part of my hand rather than on my thumb. This was a great solution (the photo above shows me playing bass sackbut with the strap) that cost about $12.00. I can see how this strap could be very helpful to people who have trouble with their index finger reaching up to the mouthpiece (the strap is fully adjustable with Velcro) or who have had tendinitis or other left hand injuries. Various manufacturers are now making this kind of strap, and it's available from many brass shops including Osmun Music near Boston.

Some players have another kind of problem which results in having to play uncomfortably. Trombones all have hands grips in a "one size fits all" configuration. Most products designed to help the left hand grip are designed for people who have small hands or who lack the strength to hold the horn comfortably. But there are people who have the opposite problem - their hands are too large to comfortably hold the horn. The standard grip causes their fingers to wrap around each other resulting in tension.

Bass trombonist Stan Taylor has developed a wooden hand grip that can be fitted on the slide which is pictured below. At 6'5" tall, Stan has large hands which led him to think about a way to retrofit his Getzen tenor trombone to be more comfortable to hold. Stan can make handgrips to order for any model of trombone and any size of hand. For more information, visit Stan Taylor's website from which you can email him about his wooden hand grip.

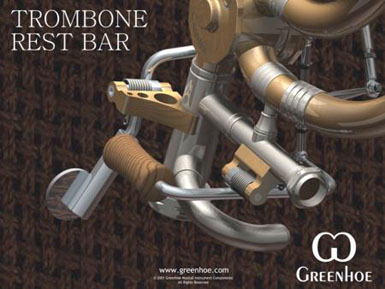

Gary Greenhoe, of Greenhoe Musical Instruments, has developed something called the "Rest Bar" which allows the fleshy part of the left hand to take more of the weight of the horn while reducing strain on the thumb. Click on the photo below to go to the Greenhoe Musical Instruments webpage (once there, click on "Retail Products" and then go to "Rest Bar") for more information about this modification. Several manufacturers are now making a product based on this principle.

Finnish bass trombonist and inventor Jouko Antere has invented a device called the Ergobone (which is also available for horn, trumpet and euphonium) which is a kind of stand/harness which supports most of the weight of the trombone while playing. This device does, in fact, significantly reduce the weight of the trombone on a player's body, with a monopod doing most of the work supporting the trombone whether in a upper body mounted "sternum strap" harness, or extended to the seat of the chair in which the player is seated. Recent studies conducted at the Royal Weish College of Music and Dance support the claim of reduced weight and reduced muscle tension while playing trombone with the Ergobone.

On its face this would seem to be a good thing. Reduced tension while playing is something players are always looking to achieve. However based on my own personal experience in using the Ergobone after a left arm injury, I remain skeptical as to whether it is a viable tool for long term playing. At the same time, I do recommend it as a useful tool to help a player who is rehabilitating from an injury.

In 2011, in preparation for surgery to repair a torn tendon in my left elbow, I purchased an Ergobone, thinking that it perhaps might be helpful as I returned to playing after surgery. The current version of the Ergobone is a significant improvement over the original version in that it has a spring mounted on it that allows the player a measure of control - but not full control - to make micro embouchure adjustments while using the Ergobone.

Post-surgery, I found the Ergobone very helpful in allowing me to do some moderate playing of the trombone without supporting the weight of the trombone in my left hand/arm. The full weight of the trombone was held by the Ergobone's monopod and all I had to do was lightly press the monopod toward my face and I could play at a moderate volume and begin to get my embouchure back in shape. As my elbow healed, I was able to hold the trombone in the traditional manner WITH the Ergobone, thereby allowing me to play almost normally without the weight of the trombone in my left hand. This was very helpful to me as I got back in shape and ready to play again in the Boston Symphony.

However, a controlled practice session with an Ergobone is very different than playing rehearsals and concerts with it. The Ergobone performs as advertised - it takes weight and pressure off your left arm and as a result reduces muscle tension while playing. However, when used in "real world" performing, the Ergobone has significant problems that, in my own experience, led me to abandon it in regular playing. Here are my observations and conclusion when using the Ergobone for extended periods of time in rehearsals and concerts:

1) Moving the trombone from a playing to a resting position is unweildy with the Ergobone. Of course, a player can leave the Ergobone with the monopod on the chair, with the instrument fully horizontal while counting rests. But this is not always practical when turning pages or for long periods of rest when it is important to get the trombone down from the playing position. One must always remember to use the slide lock to secure the instrument or your left hand must always stay in contact with the slide to prevent it from sliding off. Physical therapists agree that the most useful "resting position" for a trombonist is to get the trombone completely out of your hands and on a trombone stand while allowing your arms to naturally rest on your thighs with your elbows at an angle of greater than 90 degrees. With the Ergobone, you must keep your left arm flexed as if holding it all the time in order to keep the trombone from falling to the floor. I should say that my experience with the sternum harness was short lived - supporting the full weight of the trombone pressing against my chest was simply not possible for me. Perhaps others find the sternum strap to be useful, but my experience with it was not positive.

2) If the player does not get the trombone back down into the normal resting position, you must empty water from the water key with the horn in a horizontal, playing position. This is inconvenient in the least. Of course, emptying water from a valve section requires taking the Ergobone out of the harness or removing the monopod from the chair (see the result of this problem below, point 3).

3) Once in the resting position, getting the Ergobone back in the harness or putting the monopod back on the chair requires lifting the trombone up and putting it in position. The Ergobone weighs 14 ounces, roughly 15% added weight to my bass trombone. In my experience, lifting the bass trombone with the Ergobone attached put added pressure and tension on my left arm by the act of getting the trombone in the Ergobone playing position. The repetitive "up and down" movement of a trombone from playing to resting position with 15% more weight proved to not only inconvenient, but tiresome.

4) Putting a mute in the Ergobone with the trombone in the playing position is extremely difficult. Any trombonist knows that putting a mute in is best done with the trombone bell close to the floor so the mute has to travel only a short distance before it arrives in the bell. If one leaves the Ergobone in the playing position, the player has to hold the Ergobone with his left hand, reach down with his right hand to grab the mute, and then insert the mute in the trombone while it is horizontal. This is a distance of about four feet from mute on the floor to the bell. Then, in order to put the mute securely in the bell, your left arm has to securely grip the trombone and push against the force of the mute as it is being put in the bell. This is extraordinaly inconvenient and puts great tension on your left elbow. Because it takes a couple of seconds to get the Ergobone out of the harness or to get the monopod off the chair, it is difficult to make fast mute changes in the usual way. In the heat of playing a piece with many and rapid mute changes, the Ergobone simply is not a viable, helpful tool.

5) As a result, the Ergobone - when used in real-time, real-life orchestral playing involving playing and resting, inserting and taking out mutes, and multi-hour rehearsals and concerts - ended up causing tension and inconvenience in new ways.

There are a number of well known players who use and endorse the Ergobone for playing. I join with them in saying that the Ergobone can be a useful tool on a limited basis as a player is recovering from an injury that does not allow holding the trombone in a conventional manner. But as an aid for playing on a regular basis in performance, my personal experience - and, I might add, the experience of several other colleagues who have used the Ergobone to similarly rehab after injuries and surgery - leads me to caution against thinking that it would be useful on a day-to-day basis. Muscle tension measured in controlled clinical trials is vastly different than measuring tension, weight bearing and convenience in true performance.

Click on the photo below to go to the Ergobone website.

|

©1996-2013 by Douglas Yeo. All rights reserved. |