|

| HOME · BIO · DISCOGRAPHY · ARTICLES · RESOURCES · SCHEDULE · LINKS · INDEX |

|

| HOME · BIO · DISCOGRAPHY · ARTICLES · RESOURCES · SCHEDULE · LINKS · INDEX |

By Andrew L. Pincus

This article originally appeared in The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts) on August 14, 1998. © 1998 The Berkshire Eagle. All rights reserved.

![]()

Douglas Yeo has been bitten by the serpent, that wind instrument that catches unwary musicians in its coils.

Made of wood and named for its shape, the serpent was in common use in Europe from about 1600 to 1850. So it was only natural for Yeo, the Boston Symphony Orchestra's bass trombonist and a fellow with curiosity about things musical, to find his way from one wind instrument to another.

As a brass player, he says, "I spend my whole life playing a metal instrument that has always been inanimate." To play something made of leather-covered wood provides a connection to a different side of music.

"You feel like you're almost playing a living thing," the 43-year-old Yeo says. "Because you have to work so hard at it, you really have to fight, kicking and screaming sometimes, to get the notes to come out the way you want them to. But the fact is, the thing can be played in tune, and it can be played beautifully.

The audience at the July 31 [1998] Tanglewood Prelude Concert organized by Yeo, heard how it can go. He and eight fellow BSO wind players teamed in a program of house-hold engertainment music from the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with Yeo switching off among three serpents.

[Click HERE to view a high resolution image of the four serpent photo at right.]

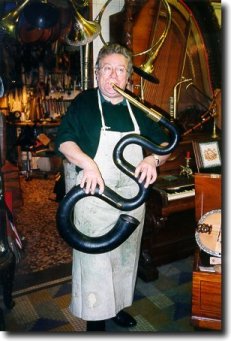

The star creepy-crawly of that show was the contrabass "anaconda," 16 feet of sycamore S-turns that stand as high as Yeo. A modern replica affectionately named "George," it was on longterm loan from its owner, a woman in Virginia. (Serpentists like to share their pets.) [NB from Douglas Yeo: In 2000, the owner of "George" decided to part with the instrument and I was pleased to welcome it to my collection.]

Yeo owns four serpents - a two foot soprano "worm," a four foot tenor instrument (the "serpet"), and two eight-foot church serpents, the standard item. One of those church serpents is a c. 1810 original, the other a 1996 replica made for him.

Yeo has been able to play the serpent in the BSO only once, but that's what got him started on the kick. It happened in 1994, when he learned the BSO was going to perform Berlioz' recently discovered Messe solenelle which calls for a serpent.

"Pretty much on a whim," Yeo set about finding and then buying a replica (which he has since sold) from a dealer in the Boston area.

I didn't even blow a note into it," he recalls. "I just bought it. So, I came back and told Lynn Larsen, our personnel manager, that I was going to play serpent in the Messe solenelle. And he said, 'Like heck you are! You're going to play that for Seiji first!'"

O.K. Over the next couple of months, Yeo practiced the part. Then he went to see Seiji Ozawa in his dressing room in Symphony Hall.

Let Yeo tell the rest:

"He came in, looked at the serpent, and the first thing he said was, 'Can you play it in tune?' As I played it, his eyes got bigger and bigger, and he said, 'Yes, yes, I like that.' That was a pivotal moment for the serpent, not just for me but for the serpent in modern history. It was the first time that a conductor of a major symphony had said yes to having serpent in a modern symphony orchestra."

After the round of performances in Boston, New York and Tokyo, Yeo got serious. He knew of a serpent concerto composed in 1989 by Simon Proctor, and he wanted to play it with the Boston Pops. But for that, he would need a "really exquisite" instrument. When he inquired, the Pops said to go for it. So he ordered his own serpent, in walnut, from the Chrisopher Monk Workshop in London, the leading modern serpent maker. The 1997 Pops performance, under John Williams, was followed by another with the Boston Classical Orchestra.

Yeo became an "evangelist" for the instrument. Wearing those robes, he points out

that the serpent was invented to accompany plainchant in France, partly because

it was less expensive than an organ.

The instrument survived into such 19th century works as Mendlessohn's Reformation Symphony and Wagner's Reinzi. It fell into disuse, Yeo says, with the invention of modern brass instruments, which got rid of the squiggles and were easier to play. Old serpents are often seen in museums and collections. Yeo says the BSO, for example, has six of them - all unplayable. In fact, most of the extant oriiginals are too broken and leaky to play.

When a well-meaning curator pulls one off the shelf in a museum and blows into it, what comes out, Yeo suggests, is a sound more commonly associated with a bathroom.

There are exceptions, such as Yeo's beautifully preserved c. 1810 church serpent. When the BSO was on tour in Paris last March, he discovered it in the shop of an instrument collector [Pictured at left is Andre Bissonnet in his shop in Paris]. It had been in the dealer's private collection, which he kept in his upstairs apartment, for 50 years.

Not only that, but he was willing to part with it because he was getting old and wanted to see his early instruments go to people who would actually play them.

"It was very expensive," Yeo says, "but it was worth it to be able to play a historic instrument in the U.S., sharing with fellow players," Who knows? it might have been the instrument used in the premiere of Berlioz' Symphonie fantastique, he says.

The serpent is clearly a conversation piece. Yeo says it has a warm sound like a "distant foghorn." P.D.Q. Bach, on the other hand, claims the thing looks like a snake and sounds like a cow.

Then there was the time when Yeo was returning to Boston in 1996 with his custom-made London serpent. At Logan Airport, the customs agent wanted proof that the strange-looking object really was a musical instrument. So Yeo took it out of the "sock" his wife had knitted as a carrying case and assembled it for the man.

"And he said, 'Play it,'" Yeo recalls. "So, I started playing the serpent in the middle of the baggage claim area.

"Well, things got very quiet. Everybody stopped talking and people started peeking. I kept looking for some kind of reaction, and he kept staring at me. I must have played three or four minutes. So I stopped playing and he looked at me and said, 'That's beautiful.'"

It was so beautiful that Yeo didn't have to pay any duty. The agent let that mooing snake through as an antique instrument.

All rights reserved. |